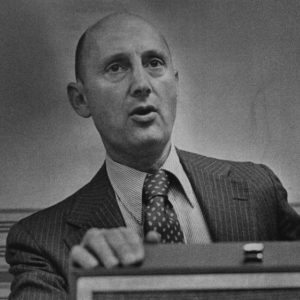

50 Years Later, Burton Malkiel Hasn’t Changed His Views on Indexing

The author of the classic ‘A Random Walk Down Wall Street’ still believes the markets are hard for any individual to beat.

Fifty years ago this January, an economist named Burton Malkiel, Rebalance Investment Advisory Committee Member, published a book calling for an innovation on behalf of the small investor. “What we need,” he wrote, “is a no-load, minimum-management-fee mutual fund that simply buys the hundreds of stocks making up the broad stock-market averages and does no trading from security to security in an attempt to catch the winners.”

Hard as it may be to believe, index investments weren’t readily available to the average saver in those days. But Dr. Malkiel was convinced that active management couldn’t consistently beat passive index investing. And in 1976 Vanguard came out with just the kind of fund he advocated. Today the sum of indexed assets is now in the trillions, and index funds, he reports, “account for more than 40% of the total invested in mutual funds and ETFs.”

Dr. Malkiel, 90 years old, still says index investing beats other approaches, and he has half a century of additional data to bolster his case, which he does in a 50th-anniversary edition of the book to be published in January. By now an investing classic, “A Random Walk Down Wall Street” has been updated to cover the many financial innovations (from exchange-traded funds to Ethereum) since it was first published. The book retains its author’s trademark blend of erudition and wit—and his insistence that markets really are efficient. The Wall Street Journal spoke with Dr. Malkiel about active vs. passive investing, his lifelong penchant for betting, and the contention of critics that indexing could be socially harmful. The conversation was held via Zoom; an edited transcript follows.

WSJ: Burt, your book recounts some of history’s worst investing manias and crashes, suggesting that stock prices are given to mad excesses in both directions. So how can you say the stock market is “efficient”?

DR. MALKIEL: What I mean by efficient is that information gets reflected quite rapidly. It doesn’t mean that prices are always right or even sane. The trouble is, nobody knows for sure whether they’re too high or too low. Even in some of the worst bubbles, some very smart people said prices made sense. And when Alan Greenspan made his famous “irrational exuberance” speech in 1996, he was years too early. You’d have been better off ignoring him.

The point is, nobody knows. And that leads to what is, I think, the essential part of efficient markets: that there are no arbitrage opportunities, no easy way to make money, without taking on a good deal of risk. The result is that markets become very, very hard for any investor to beat. Only a handful of outliers, like Warren Buffett, have done it consistently, and even they flag sooner or later. It’s almost impossible to predict who will succeed going forward. Buffett himself recommends indexing.

WSJ: And you still believe indexing is the best way for people to invest in stocks?

DR. MALKIEL: Oh, without doubt, because it works. Each year about two-thirds of active managers underperform the index, and those who outperform in one year are not the same as those who outperform in the next. S&P does something called Spiva, in which they compare the S&P indexes with active managers. And what it shows is that over a 10-year period, roughly 90% of domestic stock funds, for example, are outperformed by the index.

WSJ: If indexing is so great, how is it that endowments like the one at your own Princeton University use active management and end up capturing huge market gains while avoiding the worst drawdowns?

DR. MALKIEL: First, they learned from David Swensen, who ran Yale’s endowment, that you can get paid for illiquidity, and institutions like Princeton have endless time horizons to capture this additional premium. Second, they often do not mark to market these illiquid private investments, which makes their returns look more stable. And third, they have access to rare talents and investments that the rest of us can’t touch.

WSJ: You advocate indexing, dollar-cost averaging and diversification, and you make mincemeat of such practices as technical analysis, ESG and “smart beta.” You see cryptocurrencies as too risky. Yet you’re also an inveterate gambler. Do you buy individual stocks?

DR. MALKIEL: Look I don’t think a person who has spent one’s academic and professional life working in markets would do this without some kind of gambling instinct. I grew up a poor kid in the Roxbury section of Boston, during the Depression. And I knew the price of General Motors stock as well as Ted Williams’s batting average. I’ve always liked gambling; it’s fun. So yes, I buy individual stocks. Do I think that I am making a bigger rate of return than through index funds? I’ve never calculated it, but probably not. Will I continue to do it? Absolutely. Because it’s fun! And I read Barron’s and plow through The Wall Street Journal every day, because I enjoy it.

And I do all this knowing that it’s not very risky for me because I have a good strong retirement fund from my time at Princeton and my service on corporate boards, and that money is 100% indexed. As long as your core retirement portfolio is indexed, you can play around on the margins without much harm.

WSJ: Let’s talk about the social cost of indexing. Indexing succeeds by free-riding on the costly research and price-finding activities of active investors. What if everybody did it? Would we even have a stock market? How would we allocate capital? Doesn’t indexing reward mediocrity and excellence equally?

DR. MALKIEL: We don’t have too much indexing; we have too much active management. I think the market could function fine with just 2% or 3% of investors being active and making sure that information was reflected properly in prices.

WSJ: Other critics argue that, by giving just a handful of giant money managers major holdings in all our leading companies, ownership will prefer stasis to competition. And then there’s also the sheer concentration of power. Charlie Munger recently said of BlackRock’s CEO, “I think the world of Larry Fink, but I’m not sure I want him to be my emperor.”

DR. MALKIEL: People have suggested that big indexers would encourage a kind of collusion because they own, say, big stakes in all the airlines rather than just one. But it’s not happening yet and seems quite far-fetched. I was on the board of Vanguard for 28 years and never saw any such thing. But I think in the future, there may very well be issues of whether the investment companies should be allowed to vote the shares they control without taking account of the opinions of the ultimate shareholders they are investing for. To some extent, there’s too much reliance on the services that tell institutional investors how to vote. I think it’s not a big problem yet, but could be as the concentration gets even greater.