Six Questions to Ask a Financial Adviser About Fees

Too many retirement investors contract for services that don’t match their needs—and end up paying far more than they have to. Rebalance‘s Sally Brandon talks with the Wall Street Journal about how you can avoid falling into this overpriced trap.

Most people need financial advice at some point. But before making a deal with a financial adviser, people should know precisely what they’re paying—and what they’re paying for.

Unfortunately, that isn’t always easy. Advisers offer a range of services and fee structures, and a lot of clients can feel intimidated by both the jargon and the concepts. But if people don’t get the relationship with an adviser right at the beginning, the mistake could be compounded over years—and that can end up costing them hundreds of thousands of dollars over a lifetime.

Many advisers, for instance, offer a lot fewer services than others—but charge the same fees. Some don’t spell out in advance that clients may end up doling out additional fees each year for investments such as mutual funds.

And it may end up being a better deal for some investors to opt for a bare-bones service that just manages investments and doesn’t offer other advice. That’s especially true now that people can’t deduct certain investment management fees under the new tax law. With that in mind, here are six key questions to ask an adviser.

1. Of the fee arrangements you offer, which one best suits my needs?

It’s a basic question, and one too many people don’t ask—in part because it requires clients to figure out what their needs are in the first place.

The most-expensive option is a soup-to-nuts package that involves not only money management—taking care of all tasks like investing and rebalancing a portfolio—but also financial planning (for instance, helping clients figuring out the best way to save for college or retirement). What’s more, people with a very high net worth, perhaps $10 million or more, might have the option to have the adviser handle day-to-day financial chores like paying bills and banking.

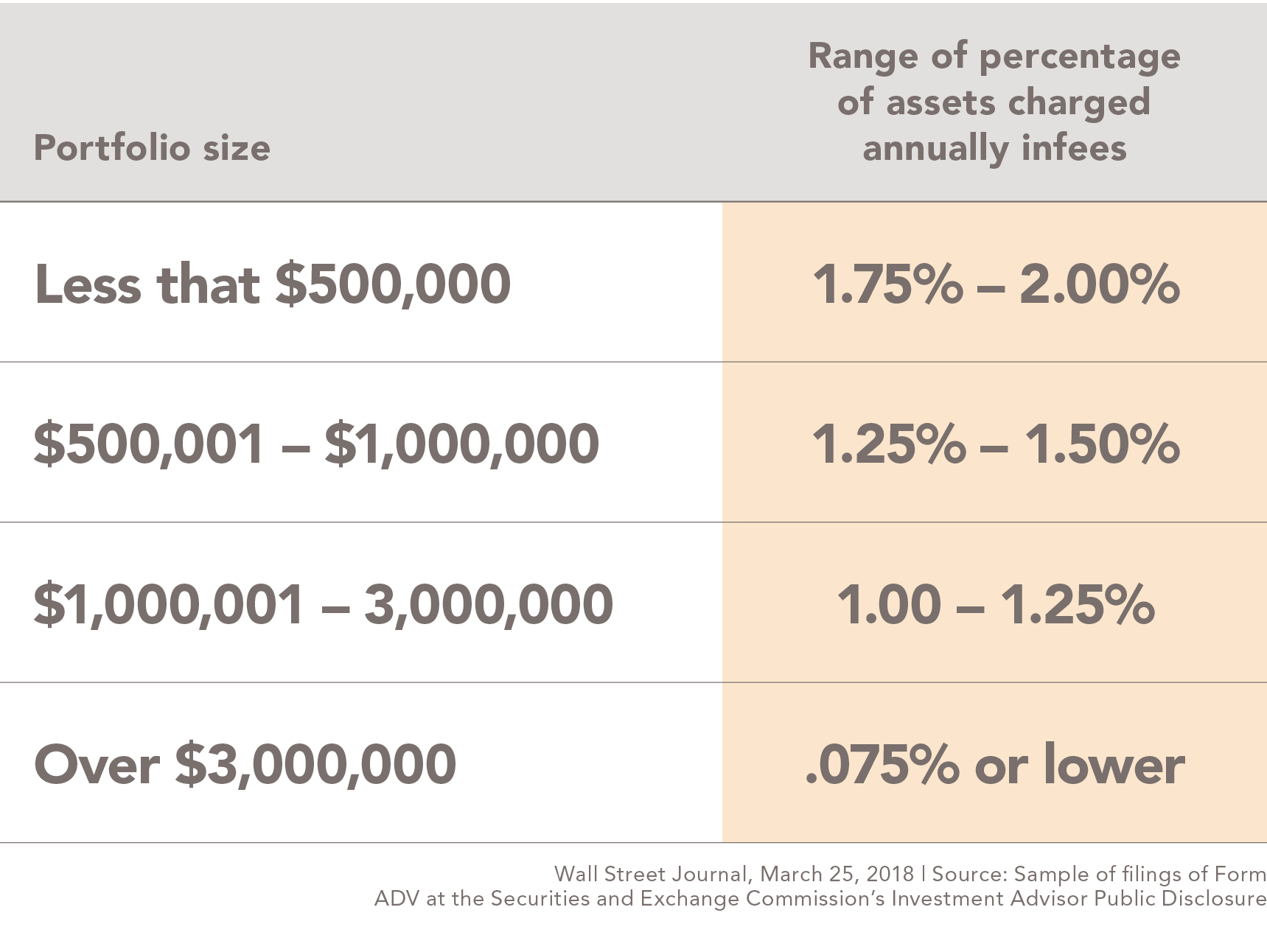

For all that, people pay a percentage of their assets under management each year. The more assets, the lower the percentage: Someone with $1 million will likely pay 1% to 1.25% annually, while someone with $500,000 or less could pay 2%.

People who don’t want all that help might find that other arrangements work better, says Michael Kitces, who heads wealth management at Pinnacle Advisory Group in Columbia, Md., and blogs on financial planning at kitces.com.

For instance, someone might not have enough assets to warrant ongoing management but might need help sorting out a particularly thorny problem—such as what to do with a bunch of inherited stock. Likewise, someone with a sizable portfolio might feel comfortable overseeing that money but want an adviser to come up with an investing plan for their retirement.

In those cases, it may make sense for people to hire an adviser by the hour, which typically runs around $150 to $350. Or, if the client and adviser decide the project will take too long for that setup, they can negotiate a one-time, lump-sum fee.

“If you have just one problem, don’t give someone your life savings to manage on an ongoing basis,” Mr. Kitces says.

Then there is an option for people who want ongoing help but not comprehensive help—for instance, people who need advice on budgeting or debt management. In those cases, a client might pay a monthly fee of $75 to $150 to sit down with the adviser for a couple of hours of coaching each month.

2. What services am I actually getting for my money?

When people turn their assets over to an adviser for ongoing money management, they may assume their fees cover a certain bundle of services. For instance, they may expect the adviser not just to make investments but also give guidance on taxes or help them analyze insurance coverage.

But many advisers don’t provide those services or others like them, says Sally Brandon, Senior Vice President of Client Service and Advice at Rebalance, based in Palo Alto, Calif., and Bethesda, Md., which advises investors on, and helps manage, individual retirement accounts. Instead, she says, advisers may primarily oversee portfolios, sell certain financial products and do little else.

Advisers lay out the services they provide in the agreements they sign with clients. But they very likely won’t list all of the things they don’t offer (and it’s very likely many clients may not read that agreement all that carefully). So clients may walk away thinking all of their needs are covered—and then find out otherwise when they face an unexpected event like a financial reversal or a divorce. That leaves them scrambling to track down another professional, like a tax attorney or accountant, and paying another fee.

To get a full picture of an adviser’s offerings, people can check the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Investment Advisor Public Disclosure website, which lets users search for advisers by name or by firm and scrutinize the so-called ADV form they must file when registering with the SEC. These forms show the services an adviser offers, along with their fee schedule and other information.

3. Can you give me a discount on fees?

Here’s a fact people should know before they enter into an agreement with an adviser: Many of them charge the same fees as others for a vastly different menu of services.

In fact, research suggests there is little correlation between the percentage of assets advisers charge in fees and the number of services a client will get for fees, says Ben Harris, an associate professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

That means it is imperative for people to get an idea of what other advisers in the area are offering for the same price—and make sure not to pay too much for too little. Likewise, they should check in with lower-cost providers of advice such as Vanguard Group and Fidelity Investments to see what they have on offer. All of this will entail a bit of legwork, but it’s well worth the time. If somebody isn’t going with the lowest-priced adviser, at the least they have some leverage when asking for a lower fee.

“There is a lot of room for negotiation here, and I don’t think many people are negotiating,” Dr. Harris says.

4. Do I really need all of your services in the first place?

Traditional advisory fees have come under siege as more players have entered the business. In most cases, they don’t offer the same level of advice or other services as traditional advisers—usually, just portfolio management—but they are much, much cheaper.

Mutual-fund giant Vanguard offers services for just 0.3% of assets annually for someone with less than $5 million. Web-based firms such as Betterment LLC and Wealthfront Inc. charge as little as 0.25% for portfolio rebalancing and other services.

Because there are so many alternatives, consumers should ask themselves how much advice they really need, says Micah Hauptman, a financial-services counsel at the Consumer Federation of America. “If you just want investment products rather than genuine advice, there are really inexpensive options.”

Who needs advice, and who doesn’t? Obviously, everybody’s situation is different, but there are some very rough guidelines. Often, younger people who have only a modest amount of assets won’t need financial advice. But someone who has been working for years and perhaps has more than $500,000 might benefit from advice on how to deploy that money—particularly if it is scattered around in different investment accounts without an overall allocation strategy. Then there are those who might want one-time advice, such as people just starting a family who need an estate plan.

One factor that is sometimes overlooked is the need to have a steady hand steering a portfolio through choppy waters, says Mark Schoenbeck, a senior executive at Kestra Financial , in Austin, Texas, which provides services to independent advisers. “Left to their own devices, some investors will abandon their plan when markets get volatile,” he says. “An adviser can remove the emotion and help prevent investors from making mistakes.”

5. Could my net costs be higher than what we’ve agreed on?

An adviser’s stated fee may be, say, 1% of assets a year. But the net cost to a client could end up being significantly higher.

Some of the financial products that end up in a client’s portfolio have high embedded fees and complex terms. Some active mutual funds have one-time fees people might pay when they buy or sell the funds. Both active funds and ETFs also have expense ratios, the annual percentage of the assets they charge shareholders for management and administrative expenses. These average from around 0.5 percentage point annually for ETFs to 1 percentage point or more for active funds.

Moreover, advisers may seek to sell the client other products, such as annuities, where the adviser could pocket a commission as high as 8%, notes Rebalance’s Ms. Brandon.

It is important to ask an adviser to get as specific as possible about additional costs, says Pinnacle Advisory’s Mr. Kitces. On his blog, he estimates that someone paying 1% of assets under management in advisory fees actually may end up having costs of more than 1.6% a year when other investment expenses are figured in.

That said, some advisers do include the additional fees in their overall charges, and those expenses often are lower when someone works with an adviser than when investing solo.

6. Could we circle back to what I pay in fees in another year or two?

If people aren’t sure initially that they want to work with a certain adviser on an ongoing basis, they could ask for a lower, “teaser” fee for the first year, says the Kellogg School’s Dr. Harris. He suggests asking, “How about giving me one year at a lower rate so I can see what you do, and then we can talk about a higher fee down the line?”

There is no hard-and-fast rule about how much of a teaser rate to ask for, Dr. Harris says. But “a one-year discount of approximately 50 basis points seems reasonable,” he adds.

Even if a client doesn’t ask for a teaser rate at the start, there may be other reasons for having a second conversation later about fees. If the client’s portfolio appreciates significantly, for instance, an adviser may be amenable to trimming the percentage of assets charged later on.

Conversely, a client may opt to pay for just a handful of services at the start, but later decide to add more after a life event such as getting married and starting a family or inheriting money, says Kestra’s Mr. Schoenbeck. “People may be working with an adviser on one issue and then realize they need a different, longer-term advisory relationship,” he says.