The End of Active Investing?

In his recent editorial for Financial Times Charles Ellis details the pitfalls of active investing, and why the average investor should look to index investing for better long-term performance.

Since index funds deliver the market rate of return through a widely diversified portfolio with no more than the market level of risk, the only justification for actively managed funds must be either more returns or less risk or both — increasingly recognised as the investment world’s version of the triumph of hope over experience.

During the 1960s and 1970s, most actively managed “performance” funds were able — more years than not and almost always over longer periods — to produce superior returns. Clients loved it, and as fees were raised, investment managers prospered. If nothing had changed over the past half-century, active investing would still be triumphantly successful. But things have changed. New companies were created, prospered, and expanded rapidly. Established ones reorganized and then prospered too. Darwinian evolution drove inferior institutional managers out of the market and strong firms made themselves even stronger. As the competitive norm rose higher during the 1980s and 1990s, the capabilities required for even moderate success continued to rise. Today, actively managed funds are not beating the market.

The market is beating them. And the long-term trend for active management is grim. The seriously distorted conventional data on the performance of active managers are now being corrected by adding back into the record the results of funds that, because they performed so poorly, had been closed or merged into other funds and then deleted from the records. This corrected data has important messages for investors.

Actively deficient

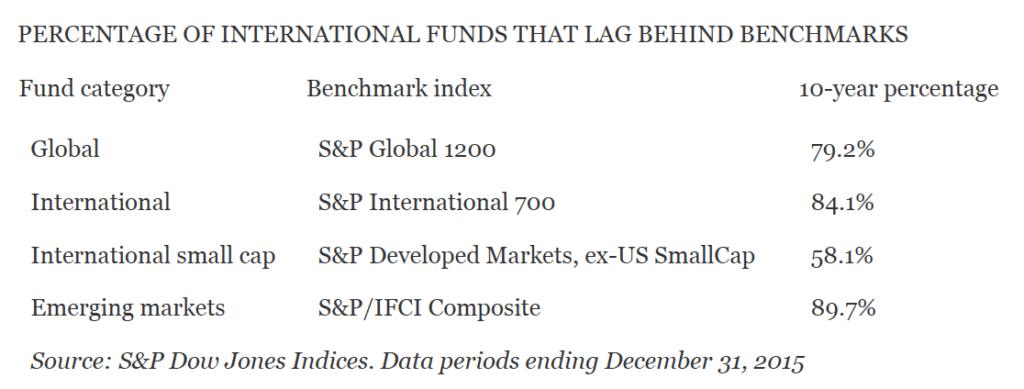

Three points are crucial. Over 10 years, 83 per cent of active funds in the US fail to match their chosen benchmarks; 40 per cent stumble so badly that they are terminated before the 10-year period is completed and 64 per cent of funds drift away from their originally declared style of investing. These seriously disappointing records would not be at all acceptable if produced by any other industry. And while these are US statistics, since international institutions dominate all stock markets, they are all moving in a similar direction. The forces of change causing these shabby results for most active managers are numerous and undeniably powerful. Over 50 years, trading volume on the New York Stock Exchange has increased 500 times — from 3m shares a day to 1.5bn (while trading in derivatives has gone from zero to now exceed the stock market in value). Investment research has increased substantially. Today’s leading securities firms have as many as 300 company analysts, industry analysts, market analysts, commodities and foreign exchange experts, economists, demographers and political analysts located in offices in major cities all over the world. The number of chartered financial analysts is up from zero to 135,000, with another 200,000 studying for the exams.

Instant communication of all sorts of information via 320,000 Bloomberg terminals, the internet, and blast faxes ensure that all investors worldwide have immediate, equal access to a global cornucopia of information, analysis and insight. With SEC Regulation FD (for fair disclosure), any investment information made available to any investor must be simultaneously made available to all investors. This eliminates what was once the “secret sauce” of active investors: getting “the first call”.

The number of professionals engaged in price discovery has, over half a century, exploded from an estimated 5,000 to over 1m. Hedge funds, the most intensive and price-sensitive market participants, have proliferated and now execute nearly half of all buying and selling. Algorithmic trading, computer models, and early versions of artificial intelligence are all increasingly powerful factors. As a result, institutional investors have collectively created a global expert information network that produces the world’s largest, most effective prediction market. The only way for active investors to outperform is to discover and exploit pricing errors by other expert professionals, all having the same information at the same time with the same computers and teams of experts having much the same talent and drive. The difficulty of sustaining a significant competitive advantage at price discovery continues to increase.

Standing out?

Curiously, the most powerful force for change has gone largely unnoticed. In the US, institutional trading has gone steadily upwards over the same half century from a market share of 9 per cent to 20 per cent to 50 per cent to 80 per cent and now more than 95 per cent. And since most retail trading is informationless “noise”, 95 per cent understates how intensively professionalised the stock market has become.

While institutional trading volumes may have advanced in an almost straight line, the difficulty of achieving superior performance when selling only to, or buying only from, near equal competitors — all active participants in the same giant, swift global information network — has been accelerating. The difficulty of outperforming the expert pricing consensus — which is the market — has been accelerating up an exponential “power law” curve.

Like the Doppler effect of an approaching train’s whistle, the impact of professionals increasingly trading only with other professionals — all nearly equally well armed and equally well-informed — has and will make it increasingly hard to outperform the market they collectively dominate as the corrected data on funds now shows.

Surely, some active managers with unusual skills or practices will continue to outperform somewhat, but they will not be competing directly with the many conventionally active managers. Nor will future “winners” be at all easy to identify in advance.

Now that most future “winners” will be easy to identify in advance if and when price volatility or a bull market in small company stocks or a bear market in large capitalisation stocks develops, we can be sure stories will appear claiming that “active is back,” filled with admiring

interviews of the new heroes of the sector. But, most of that will be due to focusing on the lucky winners while ignoring the equally unlucky losers in the wide dispersion of results so predictably caused by the statistical “law of small numbers”.

Even as evidence piles up that forceful changes are closing in and threaten to confound more and more active managers, most do not recognise the reality — or say they don’t. But, as Winston Churchill once said: “We must look at the facts because the facts are looking at us.” Like climate change and other complex systemic changes, the evidence needs careful analysis to separate long-term secular trends from medium term cyclical fluctuations around those secular trends — and both of these from meaningless short term, random statistical “noise”.

Sorting out the profound from the probable — and both of these from the ephemeral — will be sufficiently difficult for most clients that clever sellers will be able to find and merchandise highly selective, semi-plausible supportive “evidence”. We’ve seen this movie before in the way Big Tobacco cast doubt over the evidence that smoking causes cancer or the oil industry raised doubts about climate change.

The good old days

Active managers had their halcyon days in the 1960s, when they did less than 20 per cent of the trading in the US and were almost always competing at price discovery with amateur individual investors who bought or sold for reasons outside the market: to invest a bonus or inheritance received, to raise money to buy a home or pay college fees for their children. With little or no research or investment expertise, individual investors averaged just one or two trades a year.

Back then, most institutional investors were conservative mutual funds or trust divisions of banks following the precepts of personal trust investing: blue-chip “dividend” stocks held over the long term to avoid taxes and bond portfolios with laddered maturities. They were not challenging competition. In those days, it was not unusual for active managers to beat the market by 200 to 300 basis points each year. Would investors mind paying 100 basis points to get double or triple that much in higher returns? No!

Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, interest rates declined from 12 per cent to 4 per cent as the Fed, having broken inflationary expectations by pushing interest rates to record levels, let them normalise. Stock and bond prices began a long upward surge, with annual returns to investors of 10 per cent, 12 per cent and 14 per cent. Would investors mind paying 100 basis points while getting such splendid returns? No!

But today, if stock market returns over the next several years average only 6 to 7 per cent and bond returns only 2 to 3 per cent (as the consensus expects) will investor clients still be happy to pay over 100 basis point in fees when most active managers continue to underperform their own chosen benchmarks? Index funds repeatedly and predictably produce market-matching returns with no more than market-matching risk and charge less than 10 basis points. Will investors be willing to pay 90 to 120 basis points more to get active management that typically produces lower rates of return combined with more risk and more uncertainty.

Before answering that central question, readers may want to consider four phases in the past half century of active investment management.

- Phase one (1960-1980): active managers compete principally against individuals and conservative mutual funds and trust institutions. Results: 200 to 300 basis points of superior performance. Index funds get no attention.

- Phase two (1980-2000): active managers ride a strong bull market, which pleases clients greatly, but can only achieve enough incremental performance to offset their costs and fees. Index funds get some attention.

- Phase three (2000-2010): active managers no longer earn back all their operating costs and fees. Index funds experience increasing interest and demand. Switching from active management to indexing increases from a low base level.

- Phase four (2010-2017): increasing numbers of active managers — particularly larger firms that must invest mostly in large capitalisation, widely owned stocks covered by many analysts and mostly correctly priced — underperform an almost completely professionalised market, with returns averaging only 7 per cent. Objective observers conclude that fees and other costs can no longer be dismissed as “inconsequential”. Demand for low-cost indexing accelerates steadily.

Active investment managers and their clients had little or no difficulty with each other during phases one and two. Even in phase three, memories of better times in the past blended with understandable hopes for a return to past years’ favourable experiences — without insisting on any explanation of how that might actually be achieved. Focused naturally on quarter-to-quarter and year-to-year performance, where long-term underlying trends are so easily obscured by short-term cycles and “noise,” investors waited patiently, hoping for better returns.

Phase four is different. Clients are inevitably learning that the key question is not “Can we find an investment firm of super-bright, hardworking, skillful managers who will work hard for us?” The obvious, but useless answer to that question is yes! But, that is not the right question. That is, “Can we find significantly more skillful, harder working, more creative active managers?” Alas, the answer to that question for most investors is no.

Poor value

The fees conventionally described as “only 1 per cent” of assets are better seen for what they really are in a 7 per cent return market — 15 per cent of returns. Worse, try taking incremental fees as a percentage of incremental returns — both versus indexing. When you do, incremental fees for active investment management are now actually over 100 per cent — a price-to-value ratio seldom seen.

Dismal reality will not confront all active managers equally nor simultaneously. Managers least at risk will be those delivering the best results or having the best client relationships or the least demanding clients — or both. Also, managers with clearly differentiated capabilities in mathematics or clearly longer fundamental research time horizons will be under less pressure.

The greatest pressure will be on large, conventionally active managers of portfolios necessarily dominated by the same large stocks that are most widely owned and most carefully priced by the professional consensus. Meanwhile, the “vice of destiny” will continue to squeeze in on layer after layer of full-fee active managers.

Historically, most products and services that have commanded prices that produce unusually high profit margins in free, competitive markets have been unable to sustain their exceptional profitability. So far, active investing has been remarkably successful — for the active managers.

But, the remarkable success of the business — as distinct from the profession — continues to attract more and better competitors, information and technologies. This makes superior returns ever harder to achieve. And, in a lower rate of return market, this problem is increasingly visible to growing numbers of clients.

As the negative evidence continues to accumulate and the forces driving active investing’s underperformance continue to be better understood, increasing numbers of clients will realise that in toe-to-toe competition versus near-equal competitors, most active managers will not and cannot recover the costs and fees they charge.

As indexing repeatedly earns higher returns at lower cost and with less risk and less uncertainty, the world of active management will be taken down, firm by firm, from its once dominant position. The painful process will be seen in retrospect as the inevitable result of the increasingly visible impact of external and internal forces of change. As TS Eliot wrote in 1925: “This is the way the world ends. Not with a bang but a whimper.”

The power of passives

Passive funds have exploded in popularity among portfolio managers in recent years and are beginning to catch the eye of UK investors too, writes Aime Williams. The funds — which provide low-cost exposure to the market by tracking an index — have grown four times faster than their actively managed cousins since 2007.

According to Morningstar, the largest and best-selling fund available to UK retail investors is the iShares S&P 500, which has gathered nearly £60bn of cash, closely followed by Vanguard’s S&P 500 tracker, with £14bn.

Net of fees, the funds returned just over 42 per cent over a one year period and around 20 per cent over a three-year period — just under the returns of the S&P 500 index in both cases.

Fund supermarket Hargreaves Lansdown, which holds nearly £60bn of UK retail investors’ assets, says one in 10 investors hold at least one passive fund in their portfolio — up from 6 percent in 2011.

Among the most popular fund picks for DIY investors is US asset manager BlackRock’s Consensus 85 — a fund of ten other passive funds holding a range of US, UK and Japanese equity trackers, along with passive bond funds.

US low-cost fund group Vanguard launched a similar offering in 2011 — the Vanguard LifeStrategy range. Vanguard announced on Wednesday that it would cut the fees on the strategy to 0.22 per cent from 0.24 per cent as the fund hit £5bn.

Vanguard is also expected to launch its own online supermarket early this year, giving investors a chance to eliminate broker fees and gain even cheaper access to tracker funds.

Laith Khalaf, investment analyst at Hargreaves, said the price cut brought Vanguard’s fund into the price range of BlackRock’s strategy.

Other popular passive picks are FTSE trackers, which follow the blue-chip FTSE 100, mid- to small-cap 250 and the All Share, run by HSBC and Legal & General Investments.

Along with traditional passive funds, investors can access exchange traded funds — index trackers that are traded on a stock exchange.

Robo-advice platforms — which recommend portfolios of cheap ETFs to investors based on their risk appetite — have also grown in popularity in recent years.

Seeing the appeal of the model, a range of high street banks including UBS, Barclays, RBS, Lloyds and Santander have also announced plans to launch robo-advice services — all of which should give retail investors further access to passive funds.

This editorial was originally published January 20, 2017 by Financial Times