This week, we’re bringing you stories about what it costs to raise a child in 2025, and how families are making it work.

Ana Sofia Gómez Garza was ready to coast after she got into some of the nation’s top colleges, until she and her parents started considering the costs.

Brown, Cornell, Northwestern, Notre Dame and the University of California, Berkeley, were among the schools that wanted her. Few offered her need-based financial aid. Her parents had been saving, but not enough to cover full tuition for both her and, eventually, her little sister, nevermind the law school Ana Sofia also wants to attend. The cost of one year of undergrad these days can approach $100,000.

“It’s like you’re paying the salary of a recent graduate just to start going to college,” said Gabriel Gómez, Ana Sofia’s father.

Parents spend 18 years trying to decide what’s worth it for their children in a world of rising costs. For those who send their kids to college, the decision over where to go is in its own category. There is the wide-eyed optimism of launching a child into the world. There is also the potential to drain savings and rack up student loan debt. Many parents are reluctant to weigh in too much on the choice of schools, wanting to avoid tipping the scales.

Gabriel, a director at a manufacturing company, tried not to put too much pressure on Ana Sofia to pick a college based on price. What if she chose a cheaper school and ended up unhappy? But the Irvine, Calif., resident couldn’t stop himself from comparing the costs to the much lower ones in Mexico, where he and his wife, Marcela Garza, grew up and went to school.

At private nonprofit four-year U.S. institutions, the total sticker price for tuition, fees, housing and food has increased by nearly 40% over the last decade, according to the College Board. Paying four years of the annual average sticker price will run you nearly a quarter-million dollars.

Colleges have been giving more grants and discounts in recent years, meaning the net cost of college has actually been declining on average. But those funds typically go to families who demonstrate financial need.

A swath of the middle class doesn’t qualify for financial aid, but hasn’t saved enough to cover the total cost out of pocket. For them, prices are still going up.

Take Linda and Roger Liu. They consider themselves upper middle class, and they have been able to save about $160,000 in a 529 college savings account for their 16-year-old daughter, Caitlyn. “If we’re looking at tuition that’s $90,000 per year, there’s no way that’s going to cover it,” said Linda, who lives in North Caldwell, N.J.

Before running a career coaching firm for young adults, Linda was an executive at the College Board, where the “forgotten middle” would often come up. She has recently been finding that describes her finances, too. “I never thought we’d be in the situation where we’d be stressing about finances for college,” she said. “And yet here we are.”

Caitlyn, a rising junior in high school, has a spreadsheet with colleges that she is interested in. One of the columns lists cost, ranging from $33,000 to more than $90,000 a year. That will be a factor as they whittle down the number of schools heading into application season next year.

They haven’t gotten to the point of trimming the list, but nearly 80% of families report eliminating at least one school based on cost, according to Sallie Mae.

Ana Sofia, in California, applied to 20 schools, but at the time didn’t seriously think about cost. She was more focused on her high school’s theater program, college essays and her duties as student body president.

By April, 13 acceptances had rolled in. She received $11,000 in external scholarships to put toward the college of her choice.

Like many parents, hers hadn’t put their money in a 529. They would have to pay taxes on the gains in college savings they pulled from their brokerage account. That money would also have to support her 16-year-old sister, Rebeca, who wants to be a dentist.

Money was now a consideration, alongside campus culture and the quality of the international relations program she intended to enroll in. Greg Kaplan, Ana Sofia’s college adviser and founder of Kaplan Educational Group, said more students this year have been passing up acceptances to elite institutions because of the price tag.

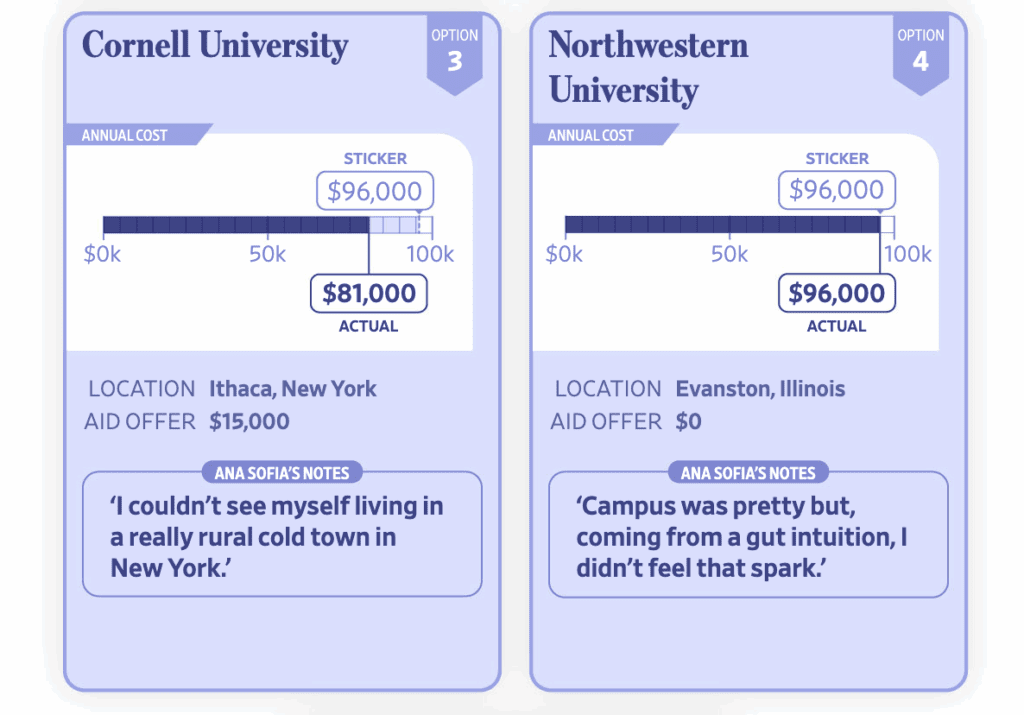

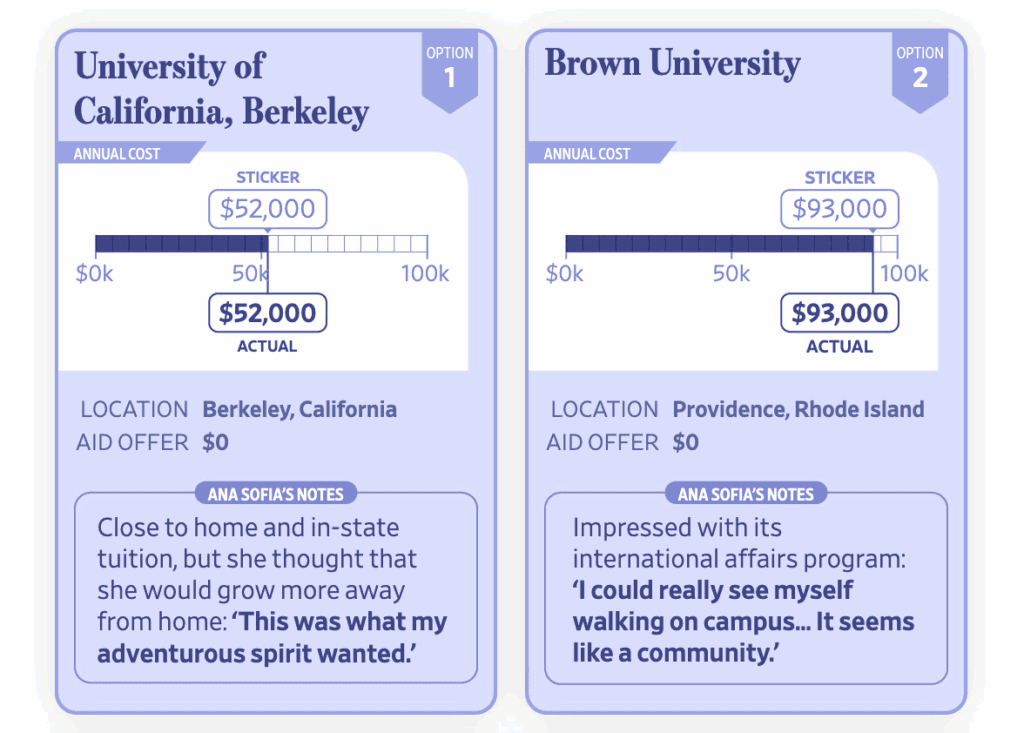

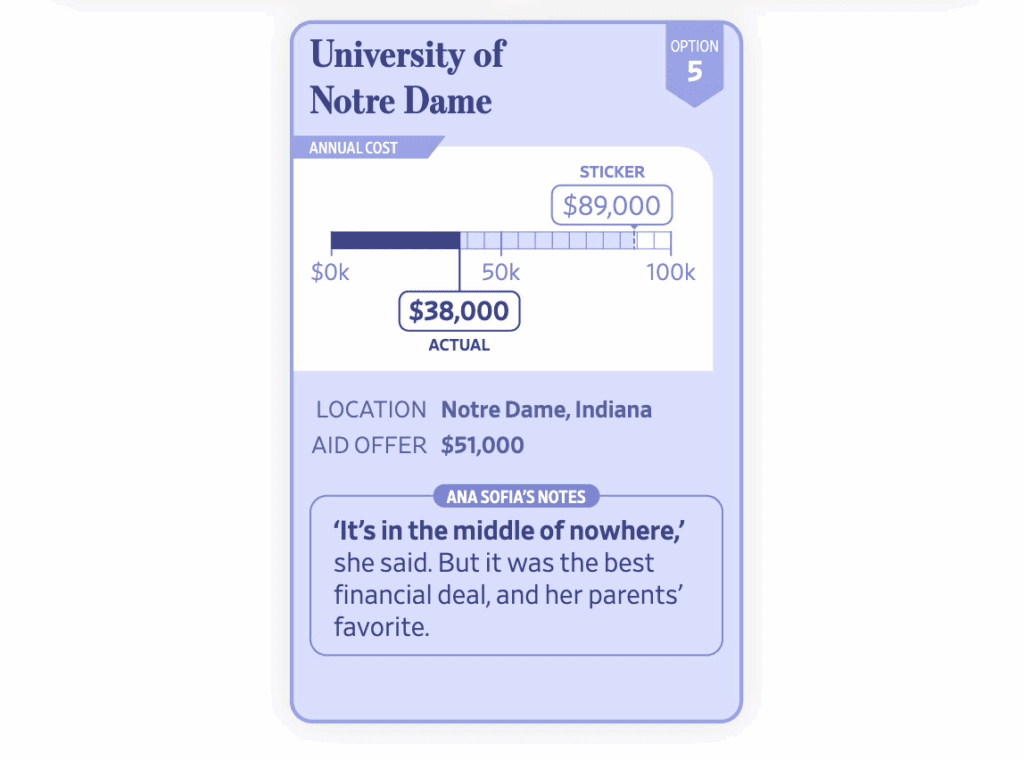

Among her acceptances, here are how the top contenders stacked up:

Note: Sticker prices include annual cost of tuition, food, housing and other fees. Actual costs are the sticker prices with the sum of all scholarships and awards subtracted.

Off the bat, she eliminated Cornell (too cold) and Berkeley (too close), and planned to visit the rest.

Her parents were rooting for Notre Dame, and not just because the school offered a $51,000 discount. They also appreciated the school’s Catholic affiliation. Gabriel could imagine himself in the bleachers at football games. Ana Sofia was hesitant.

They bought plane tickets to Chicago to visit Northwestern, and planned to take the train from there to Notre Dame. But two days beforehand, Ana Sofia told her parents she wanted to cut the Notre Dame leg. Her reasoning: “My parents might get more of an urge for me to go and it would’ve been harder to say no.”

It is still a sore spot for them. “To me that was the best one,” Gabriel said. But he said he didn’t want to interfere with her decision-making.

Neither of the two remaining schools, Brown and Northwestern, had offered her discounts. But during her campus visit at Brown, a current student told her what many families learn too late: that financial aid is oftentimes negotiable. It starts with appealing the financial aid decision.

A few days later, she did that for both schools. In the formal applications for more aid, she said that other colleges had given her scholarships and financial assistance.

Northwestern refused to give her more money. Brown asked her to provide more documentation about her family’s finances. Then, the school updated her aid, giving her a $9,000 scholarship, waiving a $5,000 health insurance fee and telling her that she would be eligible for a $3,000 work-study.

Ana Sofia accepted her offer from Brown on April 28. A month later, Brown announced that it was creating a new school focused on international relations. Ana Sofia took that as a sign she had made the right decision.

Her estimated cost of freshman year, including her scholarships and aid, will be about $65,000. She plans to work part-time jobs and paid internships in future summers to help with the cost.

Brown wasn’t originally on Gabriel’s radar. He hadn’t heard of it when he was growing up, but saw it as a good option after Ana Sofia got excited about it.

Now, he is thinking ahead to paying for law school.