This has been our message all along: instead of chasing “what is working now” like the talking heads, you need to allocate strategically, to rebalance routinely, and to think long-term!

When Boring Became Beautiful for Stock-Market Investors

By Allan Sloan, Sept. 23, 2025

Boring can be beautiful—and, it turns out, bountiful. That’s certainly the case when it comes to investors’ long-term returns on mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

What I’m talking about is one of the most interesting—and least exciting—broad-based trends in retail finance over the past 50 or so years: the rise of index funds.

Index funds are probably the most enduring and transformative innovation for individual investors since mutual funds became available to them in 1928.

When the first index fund for individuals made its debut in 1976, it started the process of making investing simpler and more understandable to regular people. No need to pick individual stocks or choose a fund manager to make investment decisions for you—just buy a stake in the whole market or a broad chunk of it with a familiar name, like the S&P 500.

Index funds also revealed one of Wall Street’s secrets—that high-cost mutual funds run by highly paid managers hardly ever outperform the market in the long run. Index funds, on the other hand, let anyone match the market’s return, minus tiny fees that these days are measured in hundredths of a percent of an investor’s holding.

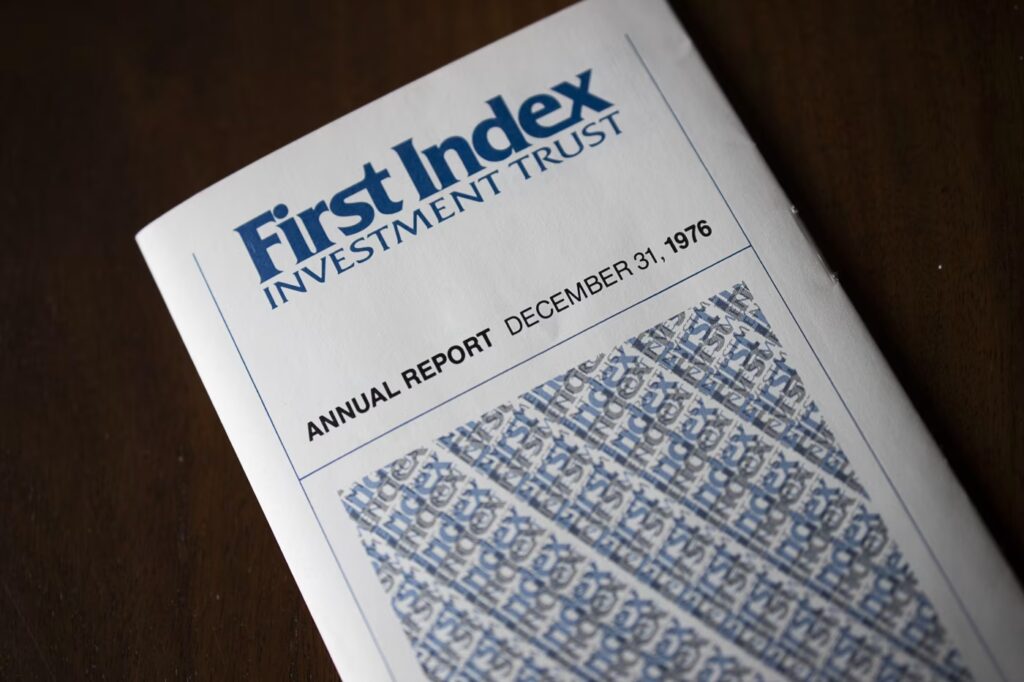

But the launch of the first index fund in 1976 was such a dog that when Vanguard Group tried to raise money for it, you could almost hear it howling. Vanguard wanted to raise $150 million from investors for the fund, then called First Index Investment Trust, but managed to collect only $11.3 million. That wasn’t even enough to buy 100 shares of each of the 500 stocks in the S&P index.

Nearly 50 years later, index funds have become a hot corner of the investment universe. As of June 30, index-fund assets were 33.73% of total fund assets in the U.S., according to fund tracker Morningstar, up from 1.77% in February 1993. (That’s the earliest date for which Morningstar has what it considers complete statistics to measure actively managed funds versus index funds.)

As of June 30, what’s now called Vanguard 500 Index Fund and its sister ETF had total assets of $1.5 trillion—that’s trillion, with a t. Vanguard’s total-stock-market index fund and its affiliated ETF had a combined $1.9 trillion of assets.

It’s all about the fees

Jack Bogle, who founded Vanguard in 1974, was obsessed with the idea of offering index funds to individual investors at a time when all the publicity—and all the cash flows from investors—went to funds run by managers whose goal was to earn above-average returns. But even though some managers beat the averages in some years, below-average returns often followed above-average years.

Bogle’s idea was that index funds, with their low fees, would give investors a higher return than actively managed funds over time because the higher costs of active funds would eat into investors’ returns

I remember rolling my eyes when the index fund was introduced—I’m 80 years old and have had money in the market since getting bar mitzvah gifts in 1957—and thinking the idea was nonsense. People called it Bogle’s Folly and even said it was somehow un-American, among other things.

These days, much of my money and my wife’s is in index funds.

Vanguard’s original First Index Investment Trust fund, renamed Vanguard 500 Index Fund in 1981, required an initial investment of $1,500, the equivalent of about $8,500 today. Its expense ratio was 0.43% of assets, more than 10 times the current expense level for the Vanguard 500 Admiral share class, but far less than the fees for actively managed funds at the time.

Because Vanguard is owned by the shareholders of its funds, not by profit-seeking outsiders, there was nothing to stop Vanguard from gradually cutting fees. Which it did, year after year.

As of June 30, Vanguard 500 Admiral shares (which require an initial investment of $3,000 and are the only Vanguard 500 share class currently accepting new investors), had an expense ratio of 0.04%—less than a 10th of First Index Investment Trust’s initial expense ratio. The ETF version of Vanguard’s 500 index fund has a fee of 0.03%.

The market expands

As the index business grew, competition emerged.

“For years, Vanguard owned the index-fund business, and it grew very slowly,” says Russel Kinnel, editor of the Morningstar Fund Investor monthly newsletter. “But over time, people picked up on how well passive funds were doing as opposed to actively managed funds.”

After stockholder-owned companies like Charles Schwab, Fidelity Investments and BlackRock decided to enter the index-fund business, it heated up and became far more competitive, with some of Vanguard’s competitors charging less for some index funds than Vanguard does.

According to the most recent statistics from the Investment Company Institute, the mutual-fund trade association, the average expense ratio for mutual funds that actively manage their stock portfolios is more than 12 times the average for funds that mirror indexes: 0.64% to 0.05%. For a $10,000 investment, that’s $64 a year for an actively managed fund, compared with $5 for an index fund.

The institute says ETFs that actively trade stocks on average charge expenses more than triple those of index ETFs: 0.44% to 0.14%. That’s smaller than the difference between actively managed and index mutual funds, but still big enough to turn into serious money over a period of years.

With fewer and fewer businesses providing current workers with company-paid pension funds these days, more people are using 401(k)s and other savings programs to invest for retirement—and taking on the risk of making their own investment decisions.

In this world, low-cost, boring index funds start out with a huge advantage over shinier but higher-cost actively managed funds. That’s why index funds are likely to keep taking market share from active funds as far as the eye can see.