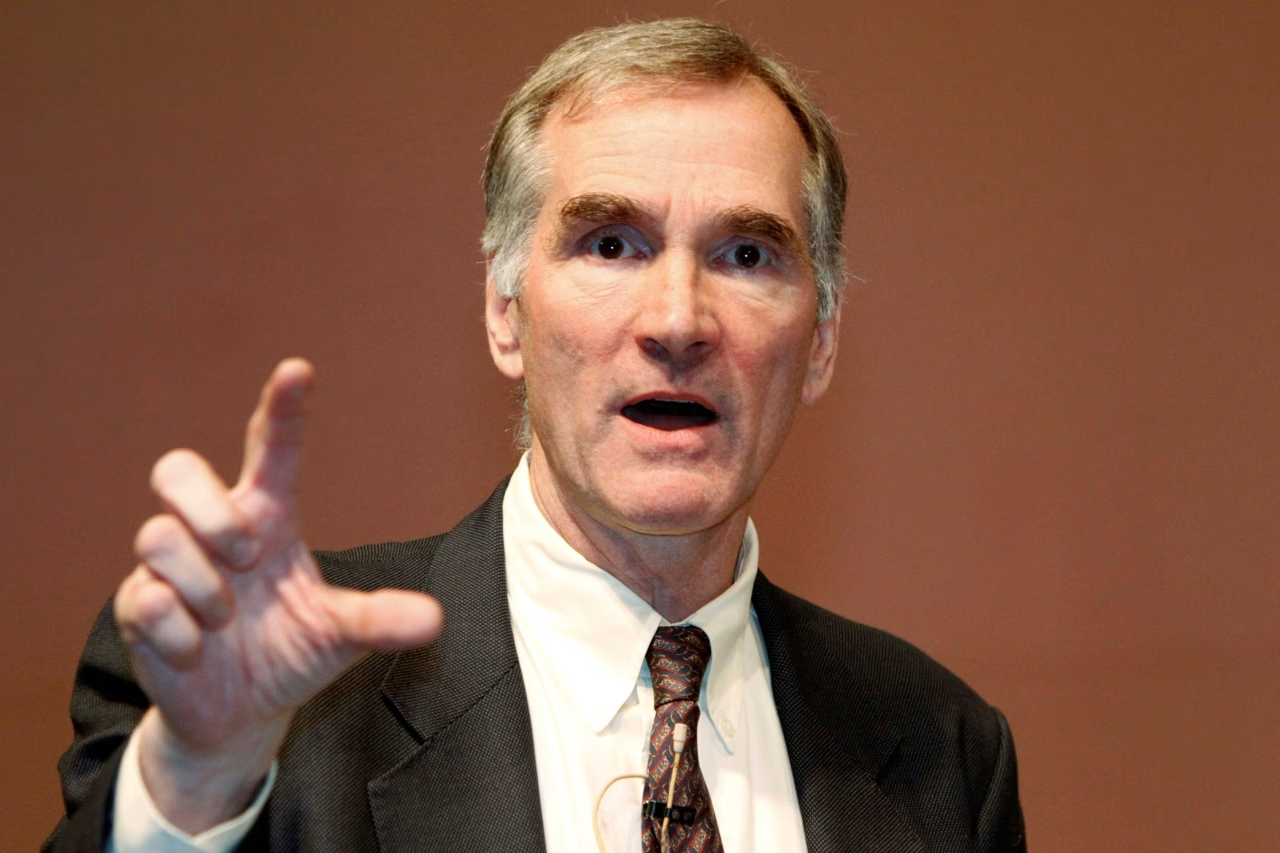

David Swensen left a lucrative Wall Street career in 1985 to manage the Yale endowment. He introduced a new investment-management philosophy and literally wrote the book describing the technique. The Swensen model worked spectacularly at Yale and at many other educational institutions. But just as the technique is now widely advertised as the optimal way for all portfolios to invest, there are good reasons to believe that it will be less effective in the future. Individual investors should especially be cautious.

The Swensen model used “alternative” assets to capture higher investment returns without accepting additional risk. Because such assets weren’t readily salable, they could be expected to provide an illiquidity premium and thus a higher risk-adjusted return. University endowments were the perfect institutional investors to employ the new model. Money given to endow a professorship, for example, would remain in the institution’s endowment forever. Only the income would be spent to cover the professor’s salary and research costs. So universities could accept illiquidity and earn a premium over the returns on publicly traded stocks and bonds.

During the decade 1999-2009, the Yale endowment performed brilliantly, earning an average annual return of 11.8%. A publicly traded portfolio of all equities earned a negative rate of return in the same period. The Yale portfolio continued to outperform more moderately through 2021, when Swensen died. But in recent years, the generous excess returns from alternative investments disappeared. In the period 2022-24, the Yale portfolio underperformed the S&P 500 by an average of more than 8 percentage points a year. And when Yale sold a significant portion of its “alternatives” portfolio in 2025, it sold at a slight discount from its carrying value, raising the possibility that valuations of some of these investments might be inflated.

One can’t use three years of data to predict the future. But since private valuations have risen to the stretched levels of public ones, the conditions now are less favorable for private returns to excel.

Two major changes now affect investment management techniques for institutions and individuals. First, the large excess returns available from “the endowment model” may no longer exist. When Swensen introduced the technique, few other investors knew about “alternatives.” Today alternatives are widely used by institutions and wealthy individuals. New investment solutions can often work well for the first to employ them. But markets learn, and extraordinary opportunities eventually get arbitraged away, just as extraordinary returns from “value” and “small capitalization” stocks became elusive.

Second, the endowment model may be less appropriate in today’s political environment. Universities have been threatened with losing billions of dollars of research support central to the institution’s mission of teaching and research. Harvard alone has indicated that more than $2 billion of research funds have been frozen by the federal government. Illiquidity threatens the institution’s ability to make temporary adjustments to offset such shocks. The new 8% income tax on the largest university endowments compounds the problem.

Different educational institutions will face different kinds of risks, but the direction of adjustments seems clear. The advantages of allocating a large share of the endowment to illiquid investments have diminished. No university could permanently offset the end of government support. The endowment would quickly be depleted. But schools could offset such shocks temporarily as appeals to reverse funding cuts are adjudicated. Broad diversification and regard for portfolio liquidity will be useful guides during a period of unusual uncertainty regarding future funding.

For individual investors and small endowments, the correct advice is even clearer. Even if alternative investments produce future excess returns, it may be impossible to reap the benefits because of extremely high fees. A typical expense charge would be an annual fee of 2% of the amount invested plus 20% of any investment earnings over a threshold return. One of the reasons Swensen did so well at Yale was that he was often able to negotiate lower fees because fund managers wanted the prestige of having Yale as an investor.

But the fees are even worse for small institutions or wealthy individuals. Since these investors would want to diversify and hold a variety of different alternatives, they would need to invest in a fund of such investments. Such funds carry large additional fees. After subtracting both sets of fees, it is highly unlikely that the investor will earn higher returns. Remember the advice of the late Jack Bogle: “In investing, you get what you don’t pay for.”

Mr. Malkiel is author of “A Random Walk Down Wall Street.”