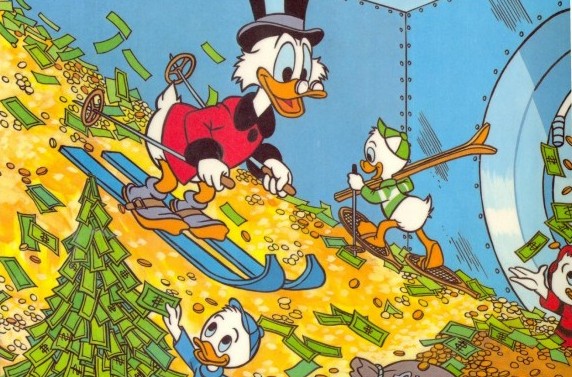

Rich people — really rich people — have an inside joke about spending in retirement: They called it “skiing.”

Not skiing as in snow skiing, but “Spending our Kids’ Inheritance.” They use it in reference to splurges, such as pricey wines, cruises through Europe, second homes, or whatever strikes their fancy.

They don’t feel bad about spending, because there’s little chance that they’ll spend so much that their own retirement is put at risk. It is truly their kids’ money, so why not?

Here’s the crazy thing. A recent Washington Post story details how ordinary savers, folks who are comfortable, perhaps, but not rich, are starting to think the same way.

This comes on the heels of the recent stock market boom. A lot of folks have crossed a threshold they once thought impossible — $1 million in their retirement plan while still working.

Fidelity Investments reports that the number of their clients with $1 million 401(k) accounts rose to 133,000 in the third quarter, up from 89,000 at the same time last year.

Overall, total retirement assets have hit $27.2 trillion, up from $11.6 trillion in 2000, according to industry data. That’s retirement plans, pension funds, everything.

The surge in investment value has financial advisors answering calls day and night from clients who want to cash out some of that stock wealth to spend now — to buy vacation homes, take once-in-a-lifetime trips and so on.

Sounds a bit like skiing, doesn’t it?

Here’s the thing about acting wealthy when you’re merely well-off. It ends in tears, just about every time.

First of all, consider what $1 million really does for you in retirement. If you assume a withdrawal rate of 4%, that level of retirement savings generates $40,000 a year in income.

If you take out $50,000 early, you’ll be taxed. If you are under 59½, add a 10% IRS penalty on top of that. So you’ll need to take out more than what you think you’ll spend — a lot more.

The total cost in taxes and penalties could easily be 40% of your targeted withdrawal. The more you take to compensate for the cost, the more you pay in taxes and penalties.

Are you ready to knick your $1 million retirement by $70,000? Do you believe stock gains in the next year will make it up?

Burt Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street and a member of the Investment Committee of my firm, Rebalance, begs to differ.

“I think one of the cardinal rules of investing is don’t try to time the market,” Malkiel says.

“And the reason is that you’ll never get it right. I’ve been around this business for 50 years and I’ve never known anyone who could time the market and I’ve never known anyone who knows anyone who could time the market. You can’t do it. It’s very dangerous.”

Fear of loss

In fact, the likely outcome is that you’ll take the money, spend it, then the market will begin a correction that will compound the negative emotional impact of your untimely withdrawal.

We know from research that people hate losing money. They hate losing much, much more than they like making money. We tend to ignore a rising stock market and then focus far too hard — to our own financial detriment — on a declining market.

We also know from market history that reversion to the mean is normal.

A few years of higher stock markets does not mean that still-higher returns aren’t possible. It’s that the market could just as easily move lower, that is, back toward its long-term average gain.

Notice that I did not say the average price, but the average gain. Stocks over time do rise in value, typically in excess of inflation. However, when stocks outpace the economy, inflation, and everything added together by several multiples, well, something has to give.

Bonds over the long run earn between 2% and 3%. Stocks in a low inflation environment earn between 7% and 8%. Compounding your savings at between 6% and 7% in a thoughtfully constructed, low-cost portfolio is a perfectly reasonable strategy.

Yet in the third quarter of 2017 the average annual return for Fidelity 401(k)s hit 15.7%, more than double the long-term expectation of such investments.

Who’s got it wrong here, and what cost? If you’re sitting on multiple millions, the question is academic.

If not, and you withdraw too much, too soon, the damage from a poorly timed early “skiing” trip could be catastrophic.