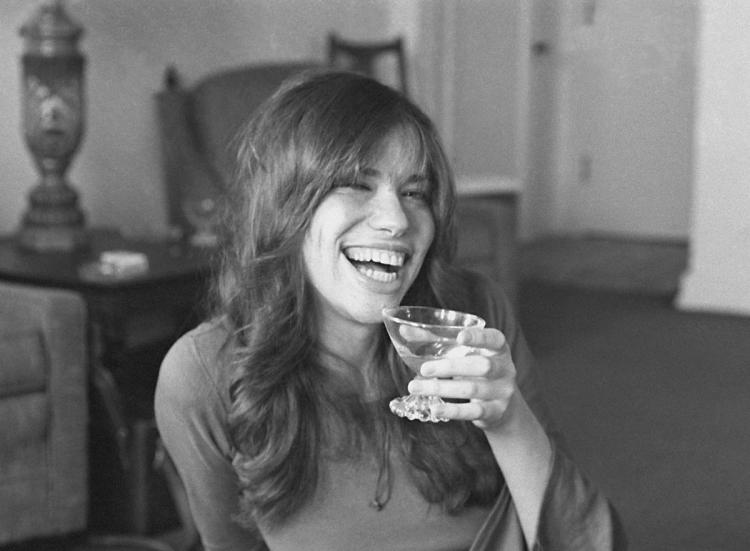

If you’ve paid attention to the radio anytime after 1972, it’s hard to avoid Carly Simon’s megahit “You’re So Vain.”

The song dresses down a former lover for his egocentricity, always checking himself in the mirror and soaking up the admiration of naive young women.

Simon reportedly wrote the song about three men, naming only one, Warren Beatty. The chorus is what hooks the listener, an earworm still recognized by tens of millions of Baby Boomers:

You’re so vain/You probably think this song is about you/You’re so vain, you’re so vain/I’ll bet you think this song is about you/Don’t you?/Don’t you?

Fun fact: Listen carefully and you’ll hear an uncredited Mick Jagger singing backup on the chorus. Once you hear it, you will never unhear it.

Like many of my fellow boomers, I love music and music history. The song got me thinking about investing, namely, the trap many of us fall into when trying to pick investments.

That trap is our own ego, the undeniable urge to measure our investment success against a competitor.

You know how this goes. Every few months or so, you check in on your portfolio and look at the return year-to-date.

Maybe your investment advisor provides a handy table comparing your personal return to a benchmark, say the S&P 500.

If you have a typical risk-adjusted retirement portfolio, you likely own a mixture of stocks and bonds. Very few investors can handle a 100% stock-only portfolio.

That’s because the emotional ride is too tough for most. A prudent advisor will counsel the investor to instead buy a mix of investments and to smooth the ride by rebalancing.

Because your portfolio is probably not all stocks, your personal return will trail the all-stock index most years, quite naturally. That can make you feel bad in a rising market.

Once stocks falter — and they will — the bond portion acts as a cushion. Your investments decline in face value, sure, but your retirement plan isn’t necessarily derailed.

Importantly, those intermittent periods of lower stock values are your opportunity to steadily invest at lower prices. Rebalancing, for instance, is selling off stocks as they rise and buying bonds.

When things turn the other way, you’ll be selling bonds to buy suddenly cheaper stocks.

It’s a proven model that adds return while reducing volatility. It has long been used by foundations and pension funds worldwide and we use it at my firm, Rebalance.

So what’s the problem? Vanity. We fall into the trap of thinking about our investments in purely personal terms.

Tune out the braggarts

Maybe your brother or sister comes home for the holidays and brags about their latest amazing stock pick. It’s up tenfold in six months!

Or perhaps you watch financial news on cable TV, salivating when you hear some options dude yammering about his killer year. Double-digit gains in a week!

You then look at your retirement portfolio that’s chugging along at 7% or 8% and sigh. If they can do it, why can’t I do it, too?

You can’t because nobody can. Your sibling is cherry-picking the big winner in his or her portfolio. Left unsaid is how many other stocks picked a year ago are still deep underwater.

Meanwhile, the options guy is not playing with his retirement money, I guarantee you. Nobody in their right mind bets the farm on anything as risky as options. And he’s cherry-picking, too.

But we’re so vain, we think investing is about us. Our personal intelligence, our skill, our worth. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Institutional investors know well that outsized gains are typically followed by years of low performance or outright losses. Concentrated bets have a way of going south. Emotions can drive you into the ditch.

Once you’re down by enough there is no recovery, no magical investment that can recoup a horrible call made due to vanity over common sense.

To paraphrase Simon, investments like that turn out to be clouds in your coffee, nothing more.