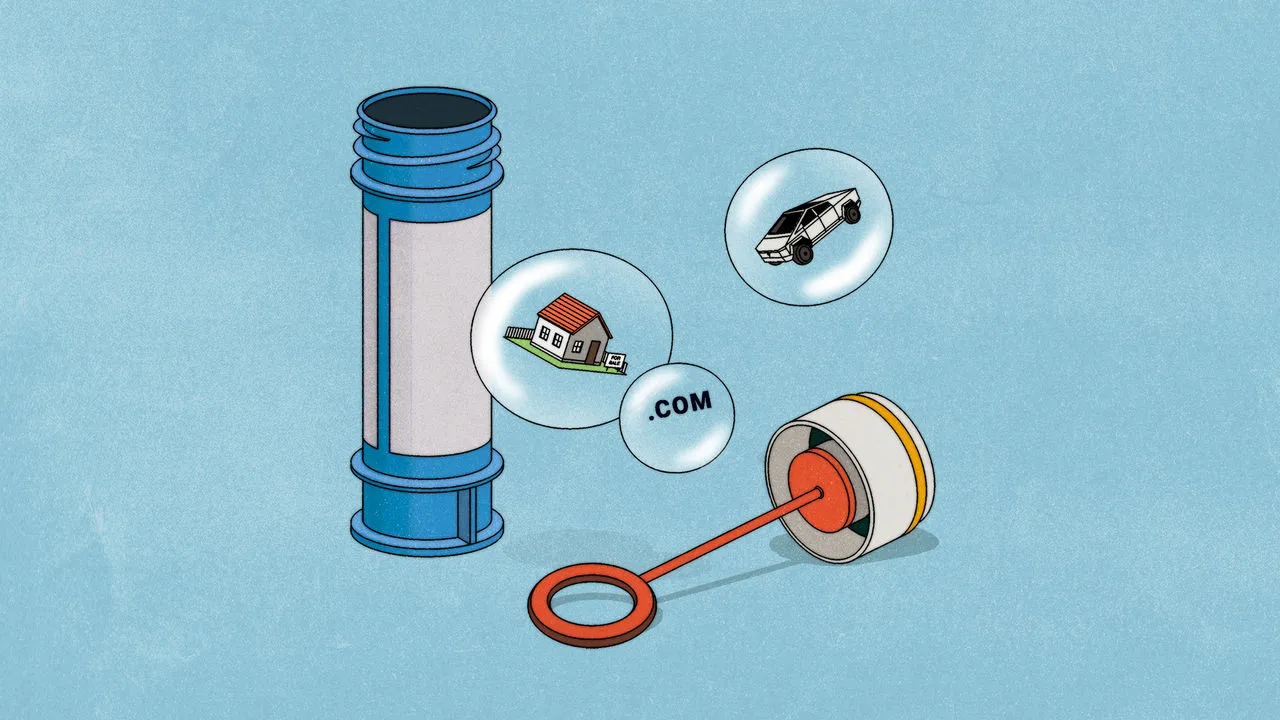

The news is flooded with opinions about whether the runup in AI-driven stocks portends a once-in-a-generation technological revolution… or is just an overhyped bubble that is going to pop.

Why Concerns About an AI Bubble Are Bigger Than Ever

By Bobby Allyn, Nov. 23, 2025

Perhaps nobody embodies artificial intelligence mania quite like Jensen Huang, the chief executive of chip behemoth Nvidia, which has seen its value spike 300% in the last two years.

A frothy time for Huang, to be sure, which makes it all the more understandable why his first statement to investors on a recent earnings call was an attempt to deflate bubble fears.

“There’s been a lot of talk about an AI bubble,” he told shareholders. “From our vantage point, we see something very different.”

Take in the AI bubble discourse and something becomes clear: Those who have the most to gain from artificial intelligence spending never slowing are proclaiming that critics who fret about an over-hyped investment frenzy have it all wrong.

“I don’t think this is the beginning of a bust cycle,” White House AI czar and venture capitalist David Sacks said on his podcast All-In. “I think that we’re in a boom. We’re in an investment super-cycle.”

“The idea that we’re going to have a demand problem five years from now, to me, seems quite absurd,” said prominent Silicon Valley investor Ben Horowitz, adding: “if you look at demand and supply and what’s going on and multiples against growth, it doesn’t look like a bubble at all to me.”

Appearing on CNBC, JPMorgan Chase executive Mary Callahan Erdoes said calling the amount of money rushing into AI right now a bubble is “a crazy concept,” declaring that “we are on the precipice of a major, major revolution in a way that companies operate.”

Yet a look under the hood of what’s really going on right now in the AI industry is enough to deliver serious doubt, said Paul Kedrosky, a venture capitalist who is now a research fellow at MIT’s Institute for the Digital Economy.

He said there is a startling amount of capital pouring into a “revolution” that remains mostly speculative.

“The technology is very useful, but the pace at which it is improving has more or less ground to a halt,” Kedrosky said. “So the notion that the revolution continues with the same drum beat playing for the next five years is sadly mistaken.”

The huge infusion of cash

The gusher of money is rushing in at a rate that is stunning to financial experts.

Take OpenAI, the ChatGPT maker that set off the AI race in late 2022. Its CEO Sam Altman has said the company is making $20 billion in revenue a year, and it plans to spend $1.4 trillion on data centers over the next eight years. That growth, of course, would rely on ever-ballooning sales from more and more people and businesses purchasing its AI services.

There is reason to be skeptical. A growing body of research indicates most firms are not seeing chatbots affect their bottom lines, and just 3% of people pay for AI, according to one analysis.

“These models are being hyped up, and we’re investing more than we should,” said Daron Acemoglu, an economist at MIT, who was awarded the 2024 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences.

“I have no doubt that there will be AI technologies that will come out in the next ten years that will add real value and add to productivity, but much of what we hear from the industry now is exaggeration,” he said.

Nonetheless, Amazon, Google, Meta and Microsoft are set to collectively sink around $400 billion on AI this year, mostly for funding data centers. Some of the companies are set to devote about 50% of their current cash flow to data center construction.

Or to put it another way: every iPhone user on earth would have to pay more than $250 to pay for that amount of spending. “That’s not going to happen,” Kedrosky said.

To avoid burning up too much of its cash on hand, big Silicon Valley companies, like Meta and Oracle, are tapping private equity and debt to finance the industry’s data center building spree.

Paving the AI future with debt and other risky financing

One assessment, from Goldman Sachs analysts, found that hyperscaler companies — tech firms that have massive cloud and computing capacities — have taken on $121 billion in debt over the past year, a more than 300% uptick from the industry’s typical debt load.

Analyst Gil Luria of the D.A. Davidson investment firm, who has been tracking Big Tech’s data center boom, said some of the financial maneuvers Silicon Valley is making are structured to keep the appearance of debt off of balance sheets, using what’s known as “special purpose vehicles.”

The tech firm makes an investment in the data center, outside investors put up most of the cash, then the special purpose vehicle borrows money to buy the chips that are inside the data centers. The tech company gets the benefit of the increased computing capacity but it doesn’t weigh down the company’s balance sheet with debt.

For example, a special purpose vehicle was recently funded by Wall Street firm Blue Owl Capital and Meta for a data center in Louisiana.

The design of the deal is complicated but it goes something like this: Blue Owl took out a loan for $27 billion for the data center. That debt is backed up by Meta’s payments for leasing the facility. Meta essentially has a mortgage on the data center. Meta owns 20% of the entity but gets all of the computing power the data center generates. Because of the financial structure of the deal, the $27 billion loan never shows up on Meta’s balance sheet. If the AI bubble bursts and the data center goes dark, Meta will be on the hook to make a multi-billion-dollar payment to Blue Owl for the value of the data center.

Such financial arrangements, according to Luria, have something of a checkered past.

“The term special purpose vehicle came to consciousness about 25 years ago with a little company called Enron,” said Luria, referring to the energy company that collapsed in 2001. “What’s different now is companies are not hiding it. But having said that, it’s not something we should be leaning on to build our future.”